Patagonia Bookshelf

Extracts from the Logs of the Thames

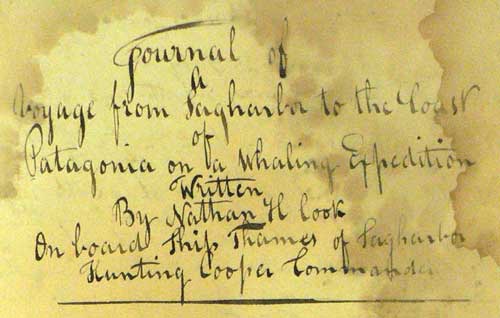

A Long Island Whaling Ship in Patagonian Waters, 1828—1832

Whalers in South American Waters

Before the development of fossil-fuel industries (coal and petroleum), European sailors hunted the whale, processing its body fat to produce lamp oil, candle wax and lubricants. By the 18th century, whalers and sealers from Britain and France were working in the South Atlantic. By the 1790s, both British and North American vessels were rounding Cape Horn to operate off the Pacific coast of Chile and Peru.

The Spanish crown guarded its South American colonies jealously, tolerating the presence of British ships on the high seas, but reacting vigorously to the establishment of land-bases, whether on the continent (e.g. Puerto Deseado) or on the southern islands (e.g. Falklands). A well-founded fear of contraband meant that any non-Spanish vessel coming to shore (in either Atlantic or Pacific ports) was viewed with suspicion, even when seeking humanitarian or technical assistance.

Recognizing the economic attraction of the whaling industry, Spain formed a royal fishing company in 1789, which operated for a few years on the Atlantic coast, but without great success. By 1820, with Spain's influence broken by the wars of independence, the newly-formed republics possessed neither the naval power nor the immediate interest to control foreign fishing. By then, hostilities having ceased between Britain and its former colony, the United States, North American whalers returned in large numbers.

Importance of Logs and Journals

When preserved, first-hand accounts by crew members, such as ships' logs, provide a special insight into the whalers' living conditions: weather, diet, chores, pastimes, and the hunt itself. Nathan Cook's journal tells of contacts with other ships: a precious opportunity for socialization and exchanging news: and, if from the same port, of sending and receiving letters.

Life on-board Ship

Of all maritime occupations, that of deep-sea whaler was probably the most hazardous and psychologically demanding. Ships and crews were away from land for months at a time, in some cases not returning to port for several years. The hunting was performed in small rowing boats, armed with nothing more than hand-thrown harpoons to confront their huge, and sometimes dangerous, victims.

In addition to the normal business of sailing, there were always plenty of other jobs to be done: sails and lines to repair, harpoons and spades to sharpen, bungs to be made for the barrels, decks to be scrubbed etc. Although Sundays were considered rest days, in practice whales could be hunted on any day of the week. The chase was not always successful: a dead whale might sink, or a live one submerge, taking the harpoon and line with it. Once captured, whales were brought alongside the ship, butchered and their blubber rendered on deck in cauldrons.

Despite the immensity of the oceans, sightings of other ships were fairly frequent: crews "spoke", and went on board when conditions permitted. Occasionally, there were surprise encounters: for example, in January 1829 the Thames sighted a large ice floe at 43° S 32° W; and in April 1831 she met an abandoned brig at 39° N 70° W, the Rebecca of Bath, which had lost its rudder.