Patagonia Bookshelf

1898

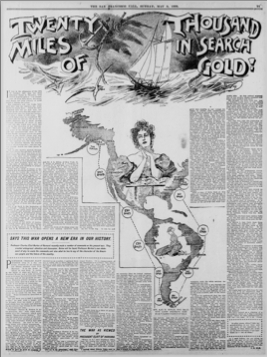

TWENTY THOUSAND MILES IN SEARCH OF GOLD !

It was in the afternoon of the 10th of October, 1897, that the little schooner

Nellie G. Thurston, with twelve hopeful gold seekers aboard, cast off from

Erie Basin, Brooklyn, and began her long journey of 20,000 miles to Alaska

far away.

It was in the afternoon of the 10th of October, 1897, that the little schooner

Nellie G. Thurston, with twelve hopeful gold seekers aboard, cast off from

Erie Basin, Brooklyn, and began her long journey of 20,000 miles to Alaska

far away.

Her journey's end was Cooks Inlet and that was the distance she must travel to reach there. Could she have mounted into the air and laid her course as the crow flies she might have alighted not very far from her destination after a flight of 5000 miles. But no such thing could be considered. The course must be laid exactly in an opposite direction and a track plowed through thousands of miles of salt water ere she could ever point her nose in the direction of her destination. Then she must baffle the howling gales of the Straits of Magellan: ride the mountain-like seas of the South Pacific; struggle across the great calms of the Pacific Ocean and run all the degrees of latitude from 50 to 60 north; or. as the sailor puts it. "the roasting tens, the warm twenties, the pleasant thirties, the roaring forties. the howling fifties and the raging sixties" before her final haven is reached.

But as she merrily plowed through the water down through New York bay, seeming to gain spirit and hope as her sails caught the fresh, invigorating sea breeze, our little crowd caught the spirit of the moment and many were the songs sung and loud were the expressions of hope and satisfaction now that we were actually upon our way to the land of shining gold, after so much hustling and bustling in preparation for our journey. Little did we think or dream of the dangers and hardships awaiting us. No more did we realize the enormity of our undertaking than if our little craft had, indeed, just taken flight for a sail through the air of 5000 miles, instead of the long and tedious voyage around the great western continent.

Now, that the greater part of our voyage is over and we are safely landed here in San Francisco, we are all determined to stick it out until we have proved our undertaking to be either a failure or a success; but as we talk among ourselves of the dangers we have passed through and the suffering we have endured we all avow that could we have known before starting what awaited us we would not have made the trip for more pure gold than any of us dare hope to find In Alaska, and I believe this to be the feeling of the majority of those who have gone before us.

But to go back to the beginning of our voyage. Owing to our hurry and anxiety to get away from New York our supplies and personal belongings had been piled in promiscuous heaps in the cabin and on the deck of our boat, and the first few days of our voyage were occupied in identifying and arranging our stuff and getting things in ship shape.

The names of our party of twelve, including eleven men and one woman, are as follows: F. E. Dowling. W. E. Story, G. H. Gunning, A. G. Fields. J. B. Ely, J. B. Wadsworth, A. G. Miles and Dr. J. L. Hiller, of New York; D. P. Nolan of Albany, E. I. Conkling of Catskill, N. Y., and Mrs. Alice J. Bolles of Hackensack, N. J. Mrs. Bolles is a wealthy and handsome young widow, who lived in a palatial residence in Hackensack, surrounded with every luxury and comfort, but who was lured away from her sumptuous surroundings by the desire for native gold and the romantic experience of digging it herself. The rest of the party, with the exception of Dr. Hiller, who was formerly a successful practitioner of Washington, D. C, and J. B. Wadsworth, who is 71 years of age and whose hair is as white as snow, are young men employed in the ordinary avocations of life, and who have gathered together our little "all" and have embarked upon this adventure with all our hearts, for better or worse.

Our boat is a two-masted schooner, measuring 87 feet over all, with a crew of seven. Her space is divided into a forecastle, galley, and main and after cabin. In the center of the main cabin is erected a framework in which the ship's stores and our outfits are stowed. Along the two sides are arranged sixteen berths for sleeping accommodation. In the center and at the end of the cargo-house is fixed our dining-table. Beneath our sleeping bunks are lockers, protruding so as to form benches to sit upon. Thus the main cabin serves as our sleeping-room, dining-room, sitting-room, smoking-room, library, drawing-room, storeroom and any other old purpose for which a room is required.

When the work of chocking away our effects and making ourselves snug for the long voyage was completed, and we were left nothing to occupy our time and thoughts, we naturally began to review our undertaking and speculate upon the future, and I believe we now did our first real sober thinking upon the subject. We had instituted a very fair library by contributing each one his selection of books, and when time began to hang heavily upon us we fell to reading; but it was easy to be seen that thoughts other than the subject before our eyes were uppermost in our minds.

As the weeks began to run by and grow into months on our voyage we began to realize with consternation that we had an extremely long and unpleasant trip before us from which there was no escape. The very first spell of rough weather had weakened our enthusiasm and now we were left without that wonderful buoyant element. There is nothing to break the monotony but an occasional school of porpoises giving us chase, or a flock of flying fish rising out of the water and scudding away before the wind, resembling a "flock" of birds more than a "school" of fish. We are so eager for any kind of excitement or change that the of "Sail, ho!" will send us all scampering up on deck with as great a hubbub as would be justifiable if we sighted the Flying Dutchman.

The kind of food used to provision a vessel for so long a voyage is necessarily bad— consisting of salted meats and dried and canned vegetables— and we begin to grow tired and sick of it. Never in all my life have I experienced such disgust and repugnance of anything as I did for the eternal monotony of eating. It seemed that we did nothing but eat and sleep, and so soon as one meal would be cleared from the table another would seem to be ready.

Sixty days after leaving New York we sighted land at Montevideo, Uruguay, and I imagine enthusiasm and excitement were equal to that on board the Santa Maria when Columbus first sighted the land of America.

The sixty days' voyage had seemed much longer to us, unaccustomed as we were to traveling by water, and our eagerness to set foot on land once more was unbounded. Just as we were about to enter the harbor, however, and when our anticipations were highest, a gale struck us and carried us a hundred miles out to sea again and for three days we were hove to. When we did finally reach Montevideo we were so sick of the confinement and monotony that we all went ashore and abandoned ourselves after the fashion of all good sailors.

After a stay of three days at this place we proceeded to the Straits of Magellan, whither we arrived fifteen days later. We had intended to stop and prospect for gold in Terra del Fuego and Patagonia, but after a general survey of the grounds and some conversation with the white settlers we abandoned the idea.

Our aim was now to get through the straits and out into the Pacific Ocean. The distance through from the Atlantic to the Pacific is 300 miles, and it proved to be the most difficult, as well as the most eventful, part of the whole voyage.

It must be understood that the tide sets strongly from the Pacific to the Atlantic through the straits, and that the wind prevails from the southwest eleven months in the year. It is not a mild, steady breeze by any means, but it ranges from a gentle zephyr to a tornado and changes from one extreme to the other so quickly that navigation by sail is next to impossible. From the day we entered the straits to the day we got out into the Pacific we had either a dead calm or a heavy gale. Never did we have a moderate breeze for more than three hours at any one time.

We were just twenty-six days making through and not a moment was lost when sailing was possible. There are anchorages marked by beacons at distances of about twenty-five miles apart, and it is considered a good day's work from one to the next.

The straits are so narrow and winding that sailing at night is impossible and time and again we failed, by only three or four miles, to reach our next anchorage after twelve hours' tacking and had to put back again. While we were anchored at Punta Arenas, which is the only town on the straits, a very severe gale came up and with both of our anchors down we began to drift across the channel direct for the rocky shore on the opposite side. At this critical moment one of our anchor chains snapped and away went anchor and chain.

We thought we were done for, but as fortune would have it our other anchor fouled a sunken wreck and held on so fast that all our efforts for the next three days failed to clear it. But it saved us from drifting ashore.

The fourth day we had a calm and somehow or other, while we were floating about, the anchor came loose of itself. This was New Year's day and we were very pleased at the manner in which the old anchor showed its patriotism.

But this was only the beginning of our troubles. Fortescue Bay was our next anchorage, and we spent one day ashore looking for signs of gold. The next day we essayed to get out, but after beating all day against wind and tide we put back there again. We repeated this operation every morning for nine days before we succeeded.

The eighth day we had got within one mile of our next port when a terrific storm came down upon us dead ahead, and we were compelled to run all the way back under bare poles. We raised sail in an attempt to go around a sharp turn, but it was blown into ribbons. These sudden storms are called by the Chileans "williwas."

There is a remarkable thing about the winds in the straits. There is a great range of mountain peaks on either side of the straits, completely walling them in, and as we sailed along abreast of the opening between these peaks the wind was so strong that we could barely carry double-reefed sails. Suddenly, as we passed the opening and came abreast of the mountain we were "blanketed" by it and would be left in a dead calm. Several times we were left thus, helpless with the wind blowing a gale overhead.

January is the midsummer month down here, but for all of this the mountain range was completely capped with huge glaciers and snow. Right beneath this at the foot of the peaks the valleys shone with all the luxurious verdure of a tropical summer.

On the 20th of January we sailed out into the open sea. As night approached we saw the last of those bristling rocks that had been such a menace to us and we were not a bit sorry.

That night a terrific gale struck us and we expected to be blown back on the rocks. We had just passed one of the small boats of the big wrecked steamer Mataura, which lay on the rocks within a few miles of us, an account of which appeared in The Call in the latter part of January. It is impossible to describe the feeling of apprehension and misery that pervaded our little community that night. Fortunately the wind hauled enough to allow us to make an offing, but the fury of the gale never abated for one moment until we actually ran clear out of its latitude, which was ten days afterward.

After this we had clean sailing right up to the line and all was buoyancy and hope as we flew along past the flying spray.

On March 1, just forty days from the straits, we sighted a sail. This was absolutely the first signs of life we had seen in all this time. To be sure it was far away from us and only the highest sails were visible, but it was life and served to break the depressing monotony. By this time our provisions were all stale and barely eatable. It's well enough for sailors and old seamen to talk about salt beef and hard tack being good enough, etc., but for we landlubbers it was worse than any picture of Klondike suffering we had seen.

In fact, the very subject of Klondike or our final destination in Alaska was never mentioned. We only hoped and prayed for San Francisco. We expected to be there within ten or fifteen days, and so great was our anxiety that it was hard to restrain ourselves from going in the rigging to look for land, though we knew it was hundreds of miles away. It was at this time that we ran into the northwest gales that kept us out so long.

On March 10 we were within three days' run of San Francisco. During the next twenty-five days we were continually tossed about by gales and high seas without one moment's rest.

Without exaggeration, our little boat was not far from being a lunatic asylum. Every conceivable thing was resorted to to occupy our minds and maintain our composure and fortitude.

Three times we were within four hours of the harbor and were blown back before terrific gales. Had our boat been the least unseaworthy she would not have survived the last gale we had.

We really had very little hope for our lives and it is an experience that I would not pass through again for any conceivable price. We were now living on salt meat and bread and the water was too stale to drink. We had to drink it in the form of tea or coffee, and it was bad at that. We knew our friends at home were anxious for us, and in our poorly nourished and depressed condition it was no wonder that now and then some poor fellow would steal away into a corner and have it out with himself.

We have tacked up a clipping of a Klondiker's letter to a San Francisco paper, which we have paraphrased to suit our own case. It is as follows:

In after years, when I take my grandchildren on my knee and tell them of my experience in Alaska, If they don't get down on the floor and howl, I will lambaste h--- out of them."

As I said before, we are going to stick it out, and we all feel sure that the worst of our experience is over, and that nothing in Alaska will be as hard to endure as was our terrible confinement of six months at sea.

J. B. ELY.